1. Current status on the participation of women in Japanese society

Since the enactment of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act for Men and Women in 1985, there have been various opinions expressed on promoting female participation in Japanese society, but it was not until the second Abe administration took office at the end of 2012 that the government began to address this issue in earnest. Specifically, under Abenomics, (1) Companies were motivated and encouraged to provide more disclosure on women's advancement, (2) The parental leave system was broadened in scope to be used by more people, and (3) Childcare capacity was expanded.

Firstly, motivating companies to promote women's advancement was fully implemented under the "Act on the Promotion of Female Participation and Career Advancement in the Workplace” that came into effect in FY 2015. Under this Act, national and local governments and large corporations are obliged to disclose information on women's advancement and to formulate and publish action plans. The number of accredited bodies has steadily increased, and an "Eruboshi" (the “L Star” award where the L stands for “Lady, Labour and Laudable”) is presented to companies with an excellent record. In line with this, the number of "Kurumin" (from the word, “Okurumi” or to “swaddle”) certifications, which certify that the company is a qualified child-rearing support company, is steadily increasing.

In addition, the government revised its Corporate Governance Code in June 2021, requiring listed companies to disclose their ideas, goals, and progress on diversity among all employees, and not just executives. Such attempts will be even more effective in boosting corporate motivation as they enhance corporate image and support the recruitment of talented human resources.

Second, Japan's parental leave system is now one of the best in the world. Both father and mother can take parental leave for up to one year until their child reaches the age of one, and 67% of the basic salary is paid for half a year from the leave date, and 50% is paid from employment insurance thereafter. Furthermore, since social insurance premiums are exempted during the leave period, the actual pay is equivalent to about 80% of the basic salary before the leave period.

On the rate of male employees taking parental leave, it is still low at 7-8%, but in recent years the rate has increased significantly from the previous 1-2%. Although men will need to further cooperate in housework and childcare, institutional and government support has become much more generous.

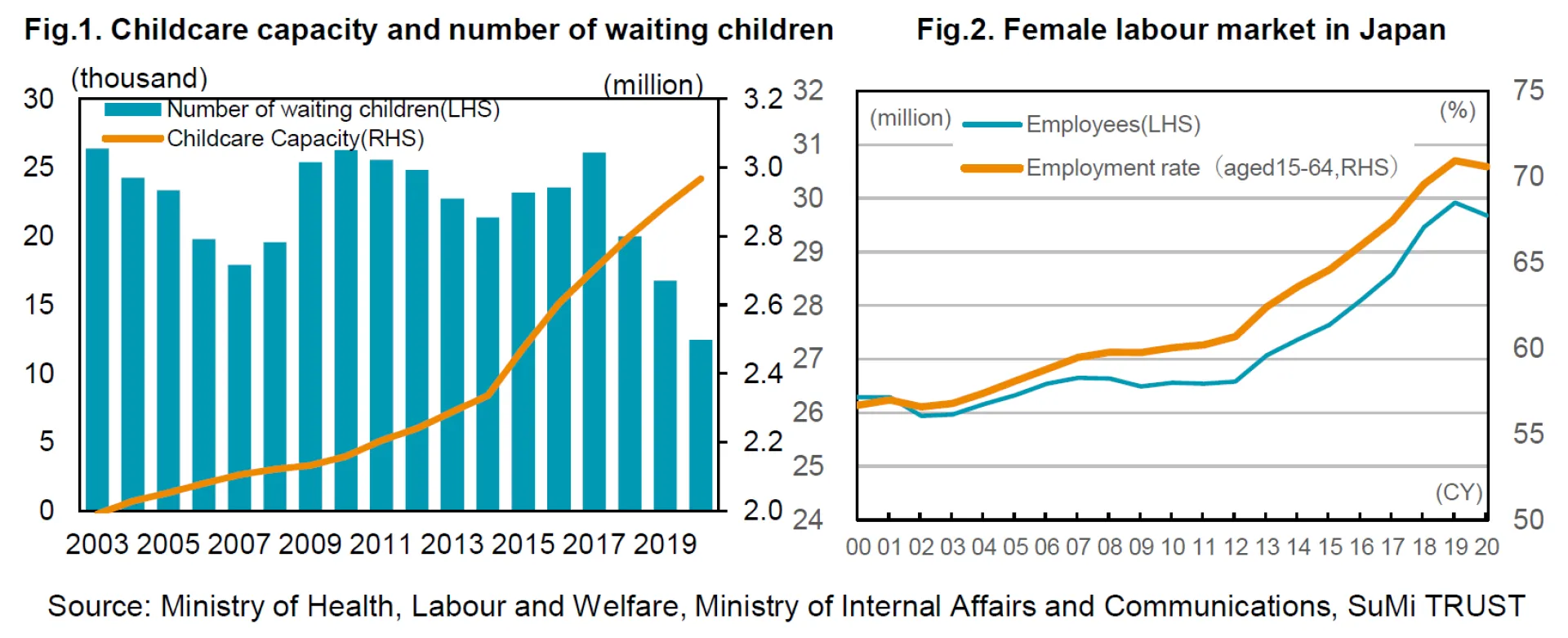

Third, Japan's childcare capacity has expanded significantly, and the number of children that are wait-listed has decreased significantly. Specifically, the former has expanded by nearly 40% in the past 10 years, and the latter has decreased by more than 50% (Figure1). Since the government's goal is to have a zero waiting-list, continuous efforts will be required in the future, but we are seeing very positive results.

We have seen some results from these policies since Abenomics was implemented, and the quantitative advancement of women has made great progress (Figure2). According to a labour force survey released by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, the number of female employees in the workforce has increased rapidly since 2013, with an average of 29.68 million in 2020. Although it fell from in the year 2020 due to COVID- 19, it has increased by more than 10% to +3.1 million compared to 2012. In addition, the employment rate, which is the number of employees divided by the population of those aged 15 and over, was 51.8% in 2020, an increase of 5.6 percentage points from 2012. And as a proportion of those aged between 15 and 64, the number rises to 70.6%, an increase of 9.9% points from 2012, reaching a level comparable to other developed countries. As the population gradually declines, it will become difficult to increase the number of those employed. We believe that the number of participating women has progressed sufficiently.

2. Challenges in the participation of women

On the other hand, the qualitative advancement of women is still insufficient. Many women are non-regular contract employees and there are major challenges in promoting women to managerial positions.

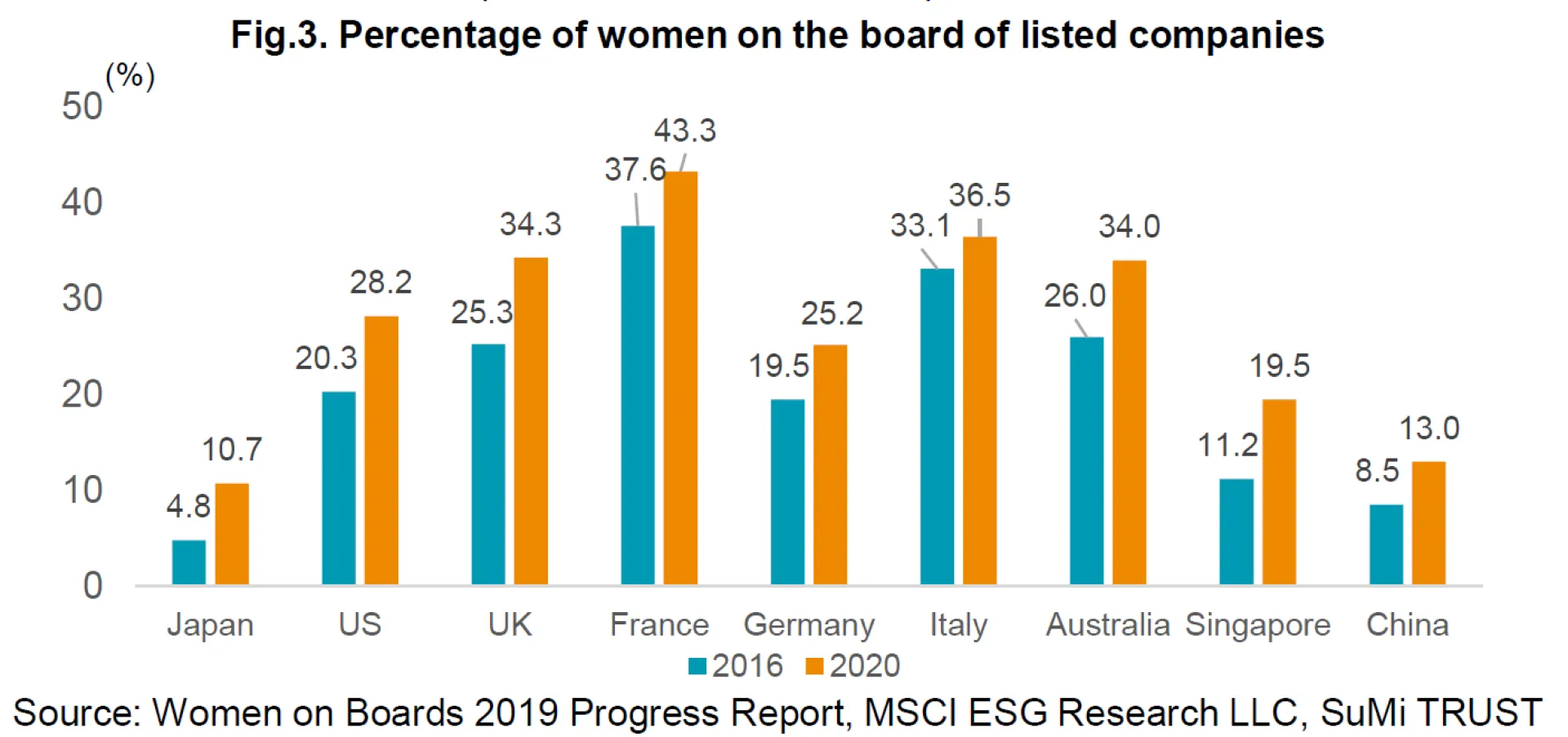

In Japan, the number of companies trying to develop female managers and promote them to directors is rising gradually, but Japan still lags behind internationally (Figure3). According to a survey by the World Economic Forum Gender Gap Index, Japan's ranking in 2021 remained an abysmal 120th out of 156 countries (121st out of 153 countries in the previous year). Although Japan is a developed country, it remains at 117th place in the "economy" field among the four fields that make up the index. This is because of the delay in promoting women to senior posts at companies and the large average wage gap between men and women. Most female directors at Japanese companies are external directors, and the development of internal director candidates among executive officers and managers has not progressed, as the pool of candidates is small. Many Japanese companies lacked the awareness to develop and train women to become executives as they tended to leave their jobs due to marriage and childbirth.

In Japan, the promotion of women has been slow even amongst public institutions. At international organisations and nations abroad, many women are active in key positions, including Kristalina Georgieva (Managing Director of the IMF), Christine Lagarde (President of the ECB) and US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, who was also Chairwoman of the Fed. But in Japan, there has never been a case where a woman became the governor or deputy governor of the Bank of Japan. Although the number of female national civil servants hired by ministries and agencies is rising every year, the percentage of women in designated positions (such as deputy directors or directors) is only about 4.4% of the total 600 posts.

Even in politics, the Biden administration has appointed half its key posts to women, and the Vice President is a woman. But under the Suga Cabinet of Japan, there are only two female ministers. The number of female members of the Japanese House of Representatives is 46 out of a total 463, or 9.9% of the total, and is ranked 166th out of 190 countries. There is an overwhelming imbalance between men and women in Japanese politics and public institutions which are not exposed to international competition.

3. Implications

The Japanese tax and employment system that have assumed that women are responsible for housework and childcare, and the unconscious and deep-rooted prejudice among middle managers and executives of companies that have been formed mainly by men, have led to the continuous prejudice against women. They have hindered the advancement of women at work, leading to a limited pool of female director candidates. Recently, the number of companies supporting women's work-life balance has increased, but because too much consideration has been given to the burden of childcare by female employees, it has resulted in depriving women of acquiring skills and chances of promotion in some cases. In order to solve these issues, it will be necessary to make systematic changes, and a renewed awareness among all executives and employees. Specifically, we require (1) efforts to promote changes in the corporate culture and attitudes among executives and employees under the strong commitment of top management, and (2) a system that enables women to balance their life stages with work. In addition, the establishment of a training system that gives women promotional opportunities. And, (3) a system to encourage men to participate in housework and childcare, and to ensure that this does not disadvantage their promotion opportunities.

Awareness and work style reform that go beyond a mere systematic change, carried out under the strong will of top management, can create a work environment where all motivated employees can work comfortably beyond gender issues, lead to corporate competitiveness and the acquisition of talented human resources even as the working population and birthrate decline. As the world changes rapidly due to globalisation and technological innovation, companies must promote diversity (including the participation of more women) to grow over the medium to long term. In other words, promoting more women is not only meaningful from an ESG perspective, but leads to sustainable growth. The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), together with the Tokyo Stock Exchange, has announced a list of public companies that excel in the promotion and advancement of women as a "Nadeshiko” (an epitome of pure, feminine beauty; an idealized Japanese woman) company (There are 44 companies as of FY 2020). These companies, on average, have outperformed the TOPIX in the last 5 years. In the stock market, foreign investors scorn Japanese companies that do not have female directors on their board. As the population declines and the wave of ESG investment rushes into Japan, it is likely that companies continuing to promote the use of women will be favoured by the market.